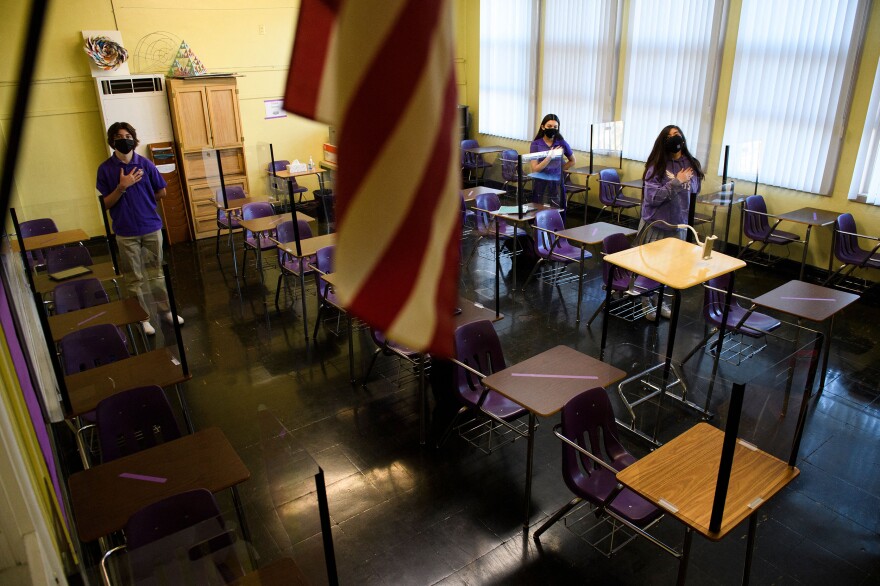

The teachers at New Hope Academy in Franklin, Tenn., were chatting the other day. The private Christian school has met in person throughout much of the coronavirus pandemic — requiring masks and trying to keep kids apart, to the degree it is possible with young children. And Nicole Grayson, who teaches fourth grade, says they realized something peculiar.

"We don't know anybody that has gotten the flu," she says. "I don't know of a student that has gotten strep throat."

At this point, it's not just an anecdote.

A study released this month in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, led by researchers from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, found that across 44 children's hospitals, the number of pediatric patients hospitalized for respiratory illnesses is down 62%. Deaths have dropped dramatically too, compared with the last 10 years: The number of flu deaths among children is usually between 100 and 200 per year, but so far only one child has died from the disease in the U.S. during the 2020-2021 flu season.

Adults aren't getting sick either. U.S. flu deaths this season will be measured in the hundreds instead of thousands. During the 2018-2019 flu season, which experienced a moderate level of flu activity, an estimated 34,200 Americans died.

Masks, distancing — and social expectations

It's not just masks and physical distance that are tamping down communicable disease, says Dr. Amy Vehec, a pediatrician at Mercy Community Healthcare, a federally qualified health center in Tennessee. It has become a serious societal faux pas to go anywhere with a fever — so parents don't send their ailing kids to school, she says.

"They are doing a better job of staying home when they're sick," Vehec says. That includes adults who may feel ill.

Isolating when feeling sick could be kept up after the pandemic. But the isolation, the distance and the masks are not working for many kids, Vehec says.

Children with speech trouble aren't seeing their teacher's mouth to learn how to speak correctly, for instance.

"I think it has been a necessary evil because of the pandemic, and I have completely supported it, but it has had prices. It's had consequences," she says. "Kids' education is suffering, among other things."

And with the COVID-19 vaccine not available to children for a while yet, it may be another year of masks in schools.

There are some experts, including researchers who are trying to improve masks, who argue that more societies should embrace widespread masking in public — as some Asian countries have. But even infectious disease experts such as Dr. Ricardo Franco of the University of Alabama at Birmingham doubt that's practical.

"I'm a little skeptical that this crisis will be enough for a widespread culture change, given how difficult it's been to achieve a reasonable culture shift in the previous months," Franco says.

The most realistic setting for lasting change to occur in may be within the health care industry itself.

Doctors and nurses didn't usually wear masks before the coronavirus emerged. Dr. Duane Harrison directs an emergency department near Nashville, Tenn., for national hospital chain HCA. He says he and his colleagues used to rag on a physician who has worn a mask since he got out of medical school.

"We used to joke and clown with him," Harrison says. "Until this."

Now that everyone is in masks, Harrison has discovered the same phenomenon as other workplaces — his people aren't calling out sick, unless it's COVID-19.

"When COVID's done, this is a practice that most of us will probably continue," Harrison says. "Because we won't be worried about runny-nose kids and elderly people who don't know they're sneezing in your face."

Some hospital systems, including Nebraska Medicine, have started to relax universal masking-at-all-times requirements for their staff. Nevertheless, even those staffers who are fully vaccinated still have to wear a mask anytime they interact with patients. Intermountain Healthcare in Utah has signaled that masks will continue to be required when a statewide mandate lifts in April.

"Is everyone going to need a break?"

But even believers in the effectiveness of masks have their doubts about the medical community keeping it up in the long run.

"The larger question is, is everyone going to need a break?" asks Dr. Joshua Barocas, who studies infectious diseases at Boston University.

Whatever the post-pandemic future holds, public health officials say the time has not yet come to drop mask requirements, because millions more in the U.S. still haven't been vaccinated against COVID-19 yet. But eventually, even doctors and nurses are ready to see smiling faces again.

"I know I'm going to need to retire my masks at some point in the future," Barocas says, "for a little bit."

This story comes from NPR's partnership with Nashville Public Radio and Kaiser Health News.

Copyright 2021 WPLN