This story originally aired on June 24, 2024.

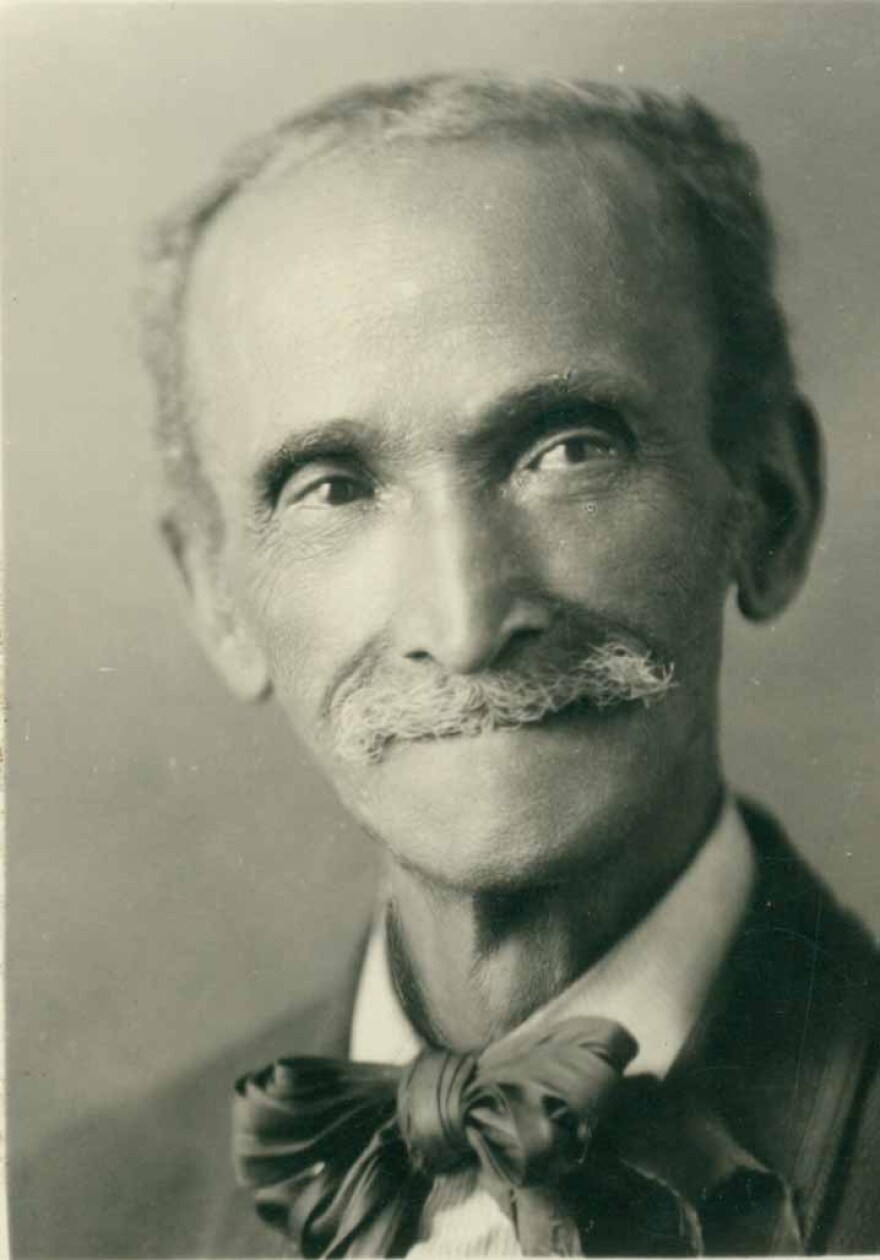

Midland has been Smallwood Holoman's home for nearly 50 years. Even though his heart is full of love for the city, he said it wasn’t always easy living here.

Holoman was one of a number of African-Americans who were recruited by Dow Chemical to come to Midland in 1975. He grew up in Virginia.

“I remember so vividly my mom was very concerned about me going to some place that she’d never heard of before,” he said. “And I told her this is a beautiful place ... I remember even telling her that, contrary to what I was used to back in my segregated community, even the garbage man and the milkman are white.”

Erin Patrice, creator and host of the Breaking Bread Village, said fellow African-Americans like Holoman have paved the way for her and others to be in Midland today. She said the city is growing and becoming more inclusive.

“To make time to celebrate and honor history and legacy is a beautiful thing,” Patrice said. “The history (of Midland) ... it’s pretty rich, and I think that a lot of times people think that there aren’t many African Americans in here. ... And there’s quite a few.”

Where Midland's African-American history begins

Jake Huss, a historical programs and exhibitions manager at the Midland Center for the Arts, said African-American people have made a large impact on Midland, bringing their talents, opening businesses and developing the city.

He said African-American people came to Midland in two waves, with the first settlers coming in the 1860s.

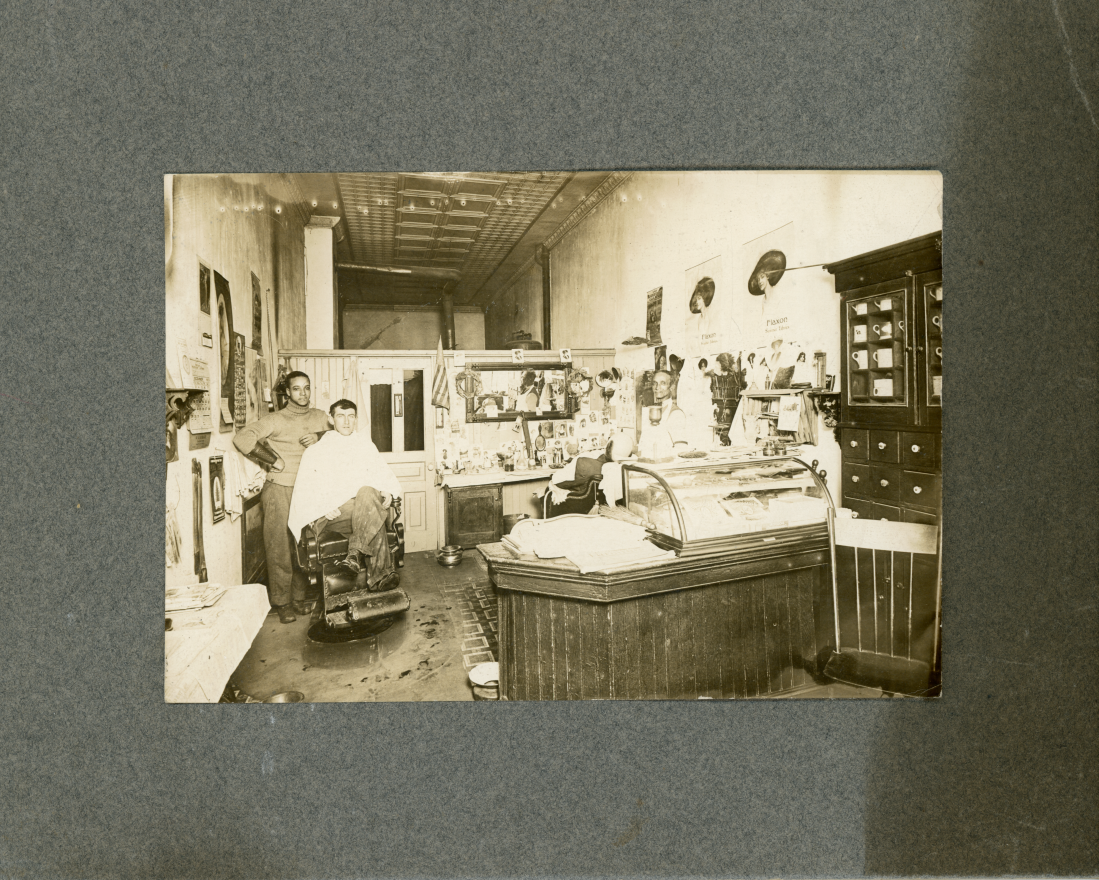

One of them was John Johnson, who settled in Midland right after the Civil War. He was hoping to work in the lumber industry, which was blooming at that time, Huss said.

But local historian Jennifer Vannette said Johnson faced racism at the Larkin Lumber Mill from other workers. That’s when the mill owner suggested Johnson become a barber.

“A barber was one of the few socially acceptable careers for Black people in this era,” said Vannette, who worked with Anti-Racist Midland on the Voices of Black Midland project, to conduct oral histories of the Black community. “Johnson came down to Saginaw for training and then returned to Midland and opened up his own barber shop. He was a well respected business owner. (But) on the other hand, (at) social gatherings and things like that, he and his family were not welcomed to participate.”

Huss said at one such gathering, a masked ball, when Johnson and his wife took off their masks, people were shocked to see them and “not necessarily made them to feel welcome at the party anymore.”

“There was also still, unfortunately, some of that racism,” Vannette said. “One of the families came home to find a noose hung in their yard ... it’s a symbol of lynching from the South, so it was a definite threat against them. There were Ku Klux Klan demonstrations in the city ... And children especially experienced (racism) in schools.”

Johnson accepted that becoming a barber in Midland was a good opportunity for him because the town was young and didn’t yet have a barber, Huss said. Johnson ran his shop for about 60 years until he died in 1932.

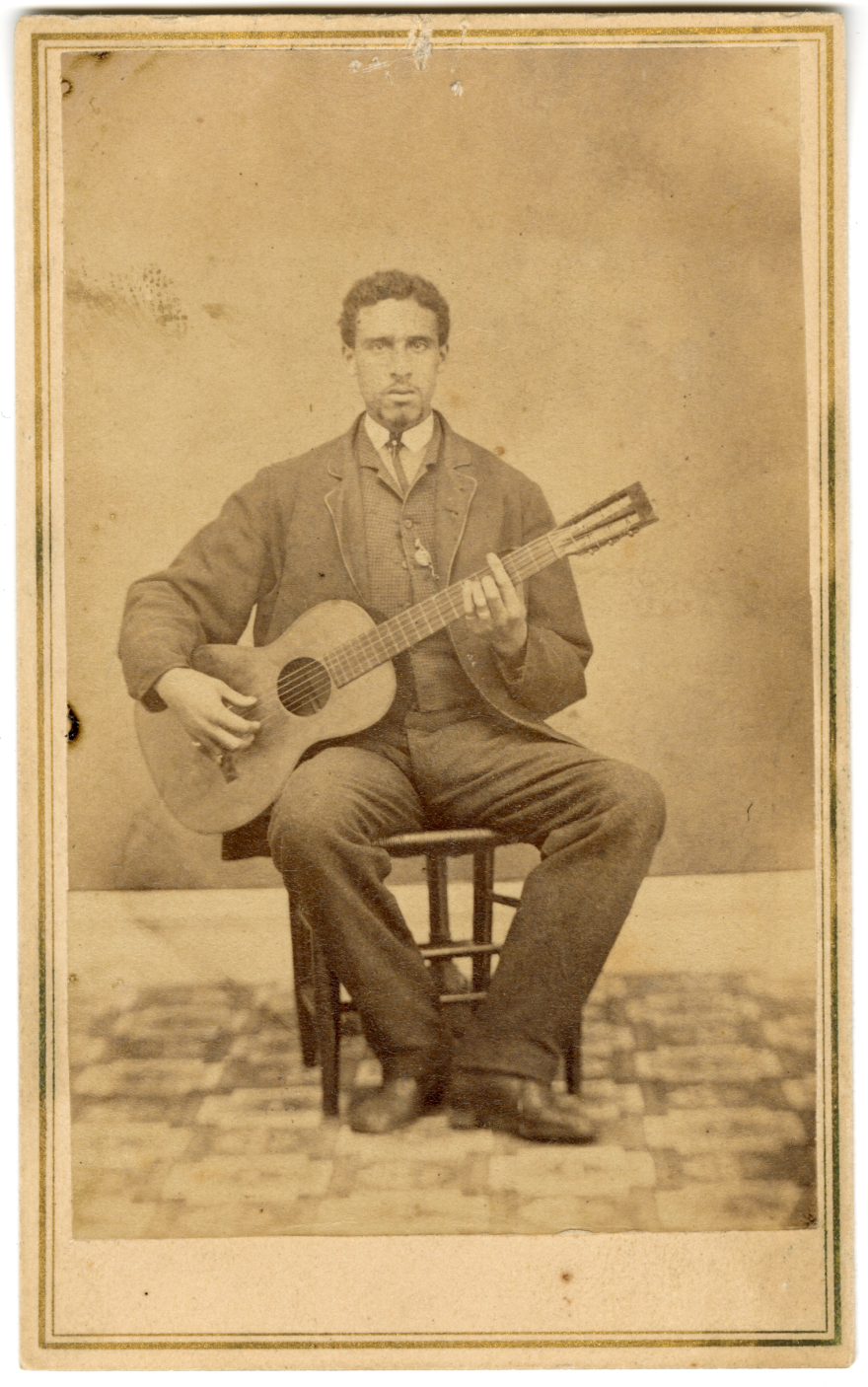

Other early Black settlers in Midland were the Highgate family, who came to the city in 1882.

“They’re an interesting family to look at pre-Midland, but their impact on Midland is very important, too,” Huss said. “In fact, Freddie Highgate is very well respected and we have a lot of different writings on him from other individuals. (He was) just a very well remembered person, very beloved in the community.

“His brother Oliver also has his own very unique and cool story here in town,” Huss added. “He was a musician. He was a barber as well ... and worked in real estate.”

After Oliver Highgate died in 1943, there were no African-American people living in Midland until the 1960s, Vannette said.

“There’s a generational gap,” she said. “Digging into that history there, there are several factors. A major factor is during that timeframe, the dominant employer was Dow and they were not hiring Black people.”

Additionally, housing covenants were put into place, stating that houses in Midland could not be sold or rented to a Black person, Vannette said.

“There was really no way to live and work in Midland if you were not white during that era,” she said.

Second wave of African-Americans settles in Midland

Over time, Dow adopted equal employment acts that had been implemented by the government, and started to recruit Black students from universities in 1960s and 1970s, Vannette said.

Huss said one of those first Black workers at Dow was Linneaus Dorman, who marked the beginning of the second wave of African-American people coming to Midland.

Holoman also remembers Midland at that time, good and bad. He even though for the most part people were nice, he did face incidents of racism.

When Holoman was walking in downtown Midland after shopping for gifts for his family, a car with young white men drove by. They pulled down the windows and yelled racial slurs at him.

“I can remember my feeling of anger because even after living in segregated communities ... white communities, that was the first time I had ever been called that name,” Holoman said. “I just got into my car and went back to my apartment, but on my way ... I kept thinking, I have nothing to feel bad about (for) being an African-American.”

A similar incident happened a few years later. Holoman was riding with his infant son on a bicycle when a group of people yelled racial slurs at them.

Holoman said he learned to never judge the whole community based on just a couple of people.

“Those are just a few knuckleheads that are in our society,” Holoman said. “They’re still here. At least that ideology among some people is still here. But again, I refuse to say (Midland) is a racist town.”

Vannette said throughout history, the African-American community has made many contributions to Midland by engaging in the community, supporting the city’s institutions by participating in activities, and giving of their talent, time and finances.

“They have also been back in the 70s recognizing that there was just a lot of misunderstanding or lack of knowledge, ignorance about Black culture, Black history, and those early people who came to work for Dow organized the Midland Black Coalition that really sought to educate,” Vannette said. “And I think we really still have that legacy. ... That educational legacy is enormous.”

Today, Patrice said Midland needs to continue connecting and supporting people. Opportunities to connect, and converse, such as the annual Juneteenth block party, go a long way to helping make the community more inclusive.

“We have tons of coalitions, organizations, nonprofits ... that are doing great work,” she said. “And if we make the effort to make sure we are collaborating and uplifting each other and amplifying each other’s voices, I think it will build the community even more so.”