"The premises covered hereby shall never be occupied by any person or persons other than the Caucasian race and Gentiles only."

That language is part of a 1926 deed for a Manchester Township subdivision, according to Justice InDeed, an organization that maps the prevalence of racist housing covenants across Washtenaw County.

Because of the federal Fair Housing Act, as well as state and local laws, housing discrimination on the basis of categories including race, sex, religion, and national origin is no longer legal.

But unenforceable language that prohibits groups like Jews or African-Americans from owning or occupying a home is still on the books in many deeds across the country. In some cases, provisions state non-whites can only occupy a home if they're working as a servant, according to Justice InDeed.

That offensive language, however nonbinding, sends the wrong message as it continues to be passed on in documents from property owner to property owner, said state Rep. Sarah Anthony (D-Lansing).

"I was hearing from homeowners... that they wanted a process to remove this discriminatory language," Anthony said. "Upholding a legacy of discrimination and hatred in many of our neighborhoods was just something that homeowners across the region just didn't want to accept."

That's why she introduced a bill that was approved by Michigan's House on Wednesday.

Under the proposal, which is now headed to the state Senate, a property owner could submit a form to have discriminatory language struck from a revised version that could be attached to their original deed. A board of a homeowner's or condominium association could also do so by majority vote.

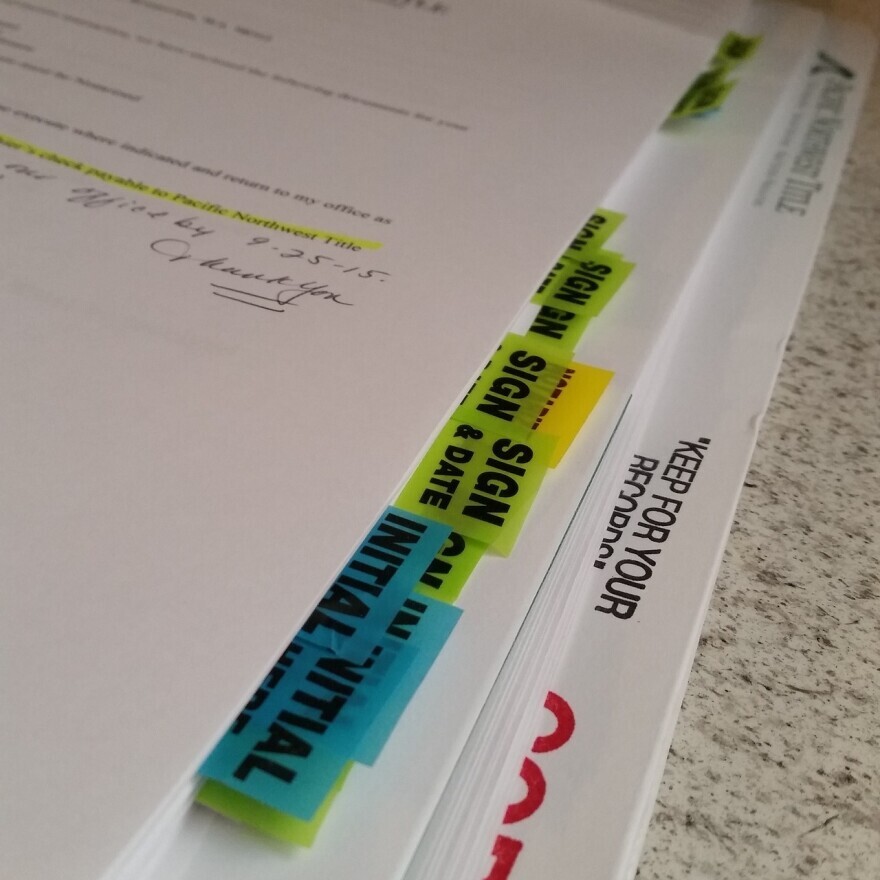

Brandon Denby leads the Michigan Association of Registers of Deeds, which supports the legislation. Sometimes, buyers or sellers are shocked when they notice decades-old racist language in documents included in the closing packet for a home, Denby said.

"You can imagine how inappropriate that is and how it must feel to someone in that closing to see that type of language in this day and age," he said.

Laura Durand, a University of Michigan law student who works with Justice InDeed, testified in support of Anthony's proposal last year. She says racist covenants are more than just a reminder of historic policies that excluded minorities from building generational wealth.

"They continue to send a message of exclusion and animosity towards non-white individuals who see them," she said during a committee hearing. "Racially restrictive covenants are like a whites-only sign at the entrance to a subdivision. They signal hostility and they cause emotional distress, even though they're legally unenforceable."

Derrick Quinney, Ingham County's first Black register of deeds, consulted Anthony about drafting the legislation, which he says has "personal significance."

"I recall back in my youth when my mother, my grandmother were working as... maids, domestics, whatever they called them at that point in time," he said. "They were going in and they were cleaning houses in areas where they couldn't live."