Right now, scientists are on a ship taking samples and measurements of the Great Lakes. They’re trying to determine how the lakes will fare this year and watching for trends, one trend, the warming climate, could mean changes for the base of the food web in the lakes. But, the researchers are not yet sure what those changes might be.

Think back to grade school when you first learned about the food web. It all starts with microscopic plant life and builds from there. Among many other things, scientists are studying how the bottom of the food web in the Great Lakes is doing.

Annie Scofield is a Life Scientist at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes National Program Office in Chicago. But she’s not in Chicago.

“Right now, I'm out on the R.V. Lake Guardian, which is our research vessel that does this spring and summer surveys, as well as a lot of other surveys over the course of the year.”

She manages the EPA’s the long-term biology monitoring program. The Lake Guardian has been visiting the lakes, taking samples and measurements since the 1980s. It can check conditions in all five lakes in about a month. When we talked, the ship was headed for Lake Erie, the fourth lake visited during this spring survey.

“Basically, we're just trying to understand what is going on in the lakes and how that's going to affect the rest of the food web as well as water quality, that's really important as a drinking water source for people.”

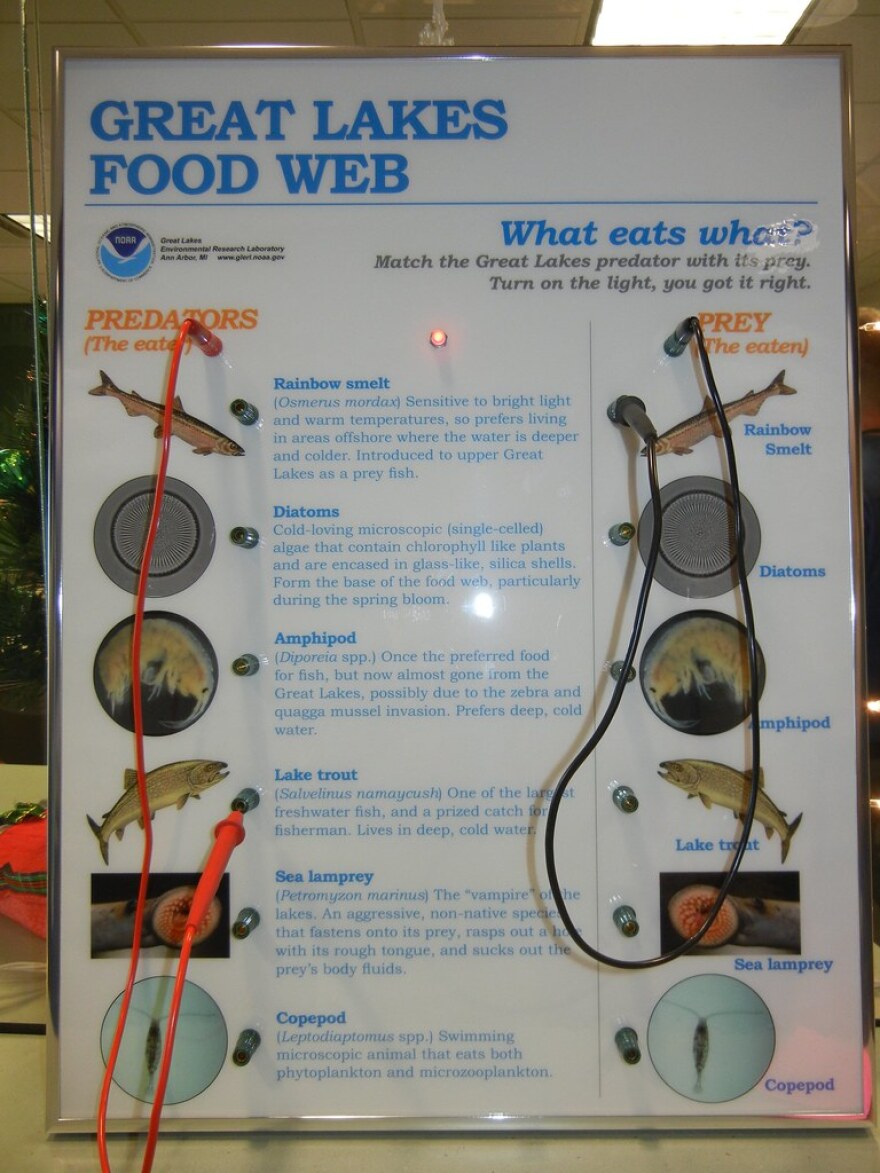

One thing she and other scientists are finding is changes in diatom populations. Diatoms are microscopic algae. Tiny organisms and some just-hatched fish like to eat diatoms. Those little fish either grow up, or they’re eaten by bigger fish, the kinds people like to eat.

Algae such as diatoms are sensitive to water quality changes. The Great Lakes National Program Offices says diatoms can serve as the first indicators of nutrient and contaminant changes such as phosphorous runoff from farm fields and lawns. And they respond to physical changes such as climate.

“One area of thought is that because of climate change, the productivity of the lower food web may decline.”

That’s Doran Mason. He’s a Research Scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab.

There are thousands of kinds of diatoms and many kinds of other algae. Mason says some of them like cold water and grow during winter. So, warming water in the lakes is bad for them.

Other kinds of diatoms and algae actually LIKE warmer water.

“Our best guess, given what we know is with warm water temperatures that are projected with climate change, that might help sustain and grow the bottom of the food web.”

The work that the scientist on that EPA research vessel are doing should help shed some light. Looking at those diatoms and other algae can help determine how the climate is changing things.

Onboard the Lake Guardian Annie Scofield says milder winters are good for those diatoms that like warmer water.

“So what we think is that we're seeing increases in this particular type of algae in response to, you know, less ice on the lakes in the winter and warmer temperatures.”

Beth Hinchey is Scofield’s supervisor back in Chicago. She says sure, maybe warmer waters are good for some of these types of algae.

“This diatoms complex is thriving, and that could signal changes in how the rest of the food web functions.

It’s a complicated business, trying to figure out how all the changes in the Great Lakes affect things. One thing can benefit some algae at the base of the food web while other algae are being harmed.”

Hinchey says if you look at diatom species overall, they’re being pressured by pollution, by climate change, and by invasive species.

“Diatoms are preferred prey for fish and the zebra mussels and quagga mussels like them as well. So we've seen big reductions in some of our diatom species since the invasion of the mussels. That points to less food for fish.”

So, the EPA’s Lake Guardian research vessel needs to keep monitoring all these vast and complex changes in the Great Lakes to try to determine what it all means for the bottom of the food web where life starts in the Great Lakes.